When your job is a physical one, the clothes you wear become more than a fashion statement – they’re part of your toolkit, and need to be up to the task. At the same time, whatever you habitually wear as a jobbing gardener becomes in effect your uniform – a part of your identity, and questions such as which material to choose for your trousers can go from minor niggle to major frustration.

Read morePreparing the way

With the days drawing out and the light levels gradually intensifying – by contrast making the dull days seem even gloomier – there’s plenty to be done in the garden now in preparation for the season ahead.

Time to break out the big guns. Well...saw.

Mid February in the garden and, while there might not be much actual growing to be done, there’s an awful lot of preparation that can be gotten on with. Not to mention purposeful striding about to be undertaken, all the while gesticulating grandly towards nothing in particular, and declaiming vastly overambitious visions of glory for neglected corners of the garden.

I have washed pots, culled old, worn pots and bought in replacements, tidied the greenhouse (after a fashion – doesn’t bear close scrutiny), and finally managed to get some heat into the structure by way of a vastly over-priced paraffin heater which, for all I can fathom, has been manufactured from a couple of old biscuit tins, but seems to do the job admirably.

No more of this, thank you very much

I’d read one terrible review after another for this type of apparatus, mostly from people who had returned to the greenhouse following the first night’s use only to find the entire place covered in thick black soot. A growing suspicion formed that the people who write these reviews can only be muppets of the highest order, who’ve failed to read the instructions and either left the wicks too long or allowed the heater to run out of fuel.

In spite of costing an arm and a leg for a bit of old tin, this little greehouse heater seems to be doing the job admirably

So far, everything’s working perfectly – and I’m pleased to have got the greenhouse to a reasonably snug and frost free state before seed sowing starts in earnest, if a little too late for several more delicate pelargoniums. (As an aside, the holders of the National Collection of Pelargoniums – the lovely people at Fibrex Nurseries – have ‘jokingly’ refused to sell me any more plants until I sort out my regime of annually culling my tender pellies over winter. At least, I think it was a joke.)

I’ve also decided to introduce some raised beds into the veg patch. My reasons are practical, rather than horticultural – chiefly that it allows me to elevate crops above small dog level, which will put an end to the thankless task of trying to chase Bill off the lettuces, his contribution to our kitchen garden adding an unwelcome piquancy to the salad dressing. Having taken the opportunity to add some timber-edged bark paths around the beds, this should drastically cut down on the amount of time we spend either weeding this part of the garden, or bemoaning the fact that it needs weeding. I’ll have to top up the bark on a reasonably regular basis – it decomposes fairly quickly, and inevitably gets mud trodden into it – but that’s a price I’m willing to pay for convenience.

Stapling in the weed control fabric to the timber path edging. I’d’ve preferred thick black polythene as it’s a bit more rugged, but this was to hand and will do the job for now.

That should make things a bit easier.

I’d been mulling the whole raised bed idea over for a week or so, when I came across further inspiration from Naomi Schillinger’s blog Out of My Shed. The sight of Naomi’s posh COR-TEN steel edging gave me raised-bed envy, and I have to admit I was sorely tempted. But I also rather like banging about with bits of wood in the shed and, since I’m also not very good at waiting about once I’ve finally decided upon a course of action, I took myself off to the local timber yard, strapped 12 three metre gravel boards precariously to the roof of the land rover, and drove cautiously home. The boards are pre-treated with a preservative called Tanalith E, which the Soil Association are happy to approve for materials used in the construction of organic veg beds (as long as the material is pre-treated, renewed applications of the preservative would have implications for organic status).

I’m intending to line the inside of the timber walls with black polythene, which should give an extra level of protection, both to the timber, and to our crops.

The process of filling the beds – pencilled in for the weekend – will have the double advantage of distracting me from sowing seeds far too early, whilst simultaneously providing a useful home for the various piles of soil heaped around the garden. Sometimes the place feels more like a bronze age burial site than anything else, though to date no dig here has yielded treasure more valuable than a few old bricks and the occasional Bakelite switch. While I’m about it, I can also add in the contents of the compost heap and the two Bokashi bins we banished months ago to the courtyard beyond the back door, for offences to olfactory decency. Lucky, lucky veg.

All of which activity feels revoltingly timely. Which is just as well – spring is on its way, and by then any feeling of being on top of things in the garden will be a distant memory.

Shopping for seeds

There’s nothing quite like the satisfaction of growing the plants from your garden from seed. The only trouble is, at this time of year I’ve a tendancy to overestimate the size of my greenhouse whilst underestimating the amount of time and effort that will be involved. Still, I like to think I’m doing my bit to keep the horticultural economy ticking over.

We gardeners are spoilt creatures. There are so many ways for us for us to get our kicks. Take the business of acquiring new plants, for example. There’s the sheer delight of wandering through a plant show, reveling in the variety and quality of the wares on display, and returning home with a pot or two (or three) containing those beautiful, expertly grown specimens that simply refused to be left behind. Then there’s the joy of the unexpected gift from a green-fingered friend – when you just happened to admire her fancy Aquilegias within earshot – freshly dug from the garden, plunged into whatever container comes first to hand, and thrust into your arms with a generosity and kindness for which your half-hearted protestations are no kind of match at all. And then there’s that whole other panoply of experience, the fairground of emotions that accompanies the process of raising your own plants from seed. The highs and lows of elation and despondency are enough to rival any roller-coaster ride, the excitement we feel at a crop’s successful germination, the appearance of the first seed leaves, and the healthy bulking up of each plant, all more than tempered by concerns over compost choice, should you prick out or sow in modules, watering and feeding regimes – not to mention the thorny issue of whether or not your neighbours can be trusted to tend the things should you be crazy enough to go on holiday while your infant plants are still at a vulnerable stage.

But before all the angst, comes the weeks and months of happy anticipation – otherwise known as winter – during which we pour over seed catalogues, envisioning how our greenhouses will look in the spring, and our gardens shortly thereafter, bursting with verdant wonders raised through our own skill and guile from tiny packets of dust and crumbs. We pride ourselves on the wisdom and prudence with which we manage the household resources, cannily opting to grow plants from seed at a tiny fraction of the outlay that it would cost to obtain potted stock, and then promptly buy far more varieties than we have space to grow or time to manage.

I’ve been doing just this. I’m usually a little later than some getting started, but I like to think I make up for lost time with the ridiculous ambition of my plans. Actually, last year, I decided to exercise restraint. Coupled with an awful year with unreliable peat-free composts, that attempt at moderation was decidedly unsatisfying, so we won’t be doing that again. This year, it’s back to business as usual, and I’m all set to Go Large or Toddle Off Homeward – if you’re going to fail, you might as well do it with spectacular aplomb. Consequently, I’m still in the process of ordering far too many seeds, and the first batch arrived a few days ago.

These were from Ben Ranyard at Higgledy Garden. The arrival of a parcel from Higgledy is always something of a red letter day – the brown envelope addressed in Ben’s generous looping hand, the red logo rubber-stamped on each of the matching seed packets, and the jolly handwritten note – little details that delight, and that’s before even considering the handful of slumbering potential contained within each small brown paper package. It’s enough to make you come over all unnecessary.

I shall have my work cut out for me this spring. I don’t sow until March – I find domestic conditions tend to favour straggly seedlings if sown this month – and in addition to my Higgledy bounty, I’ve another order to place from elsewhere, plus whatever I have left over from previous years – a not inconsiderable collection which needs to be sorted into the potentially viable and the probably defunct. Best get on with it.

My Higgledy shopping basket contents: Zinnia 'Mammoth', Sweet Pea 'Winston Churchill', Sweet Pea 'Beujolais', Sweet Pea 'Jilly', Reseda luteola, Helianthus 'Vanilla Ice', Helianthus 'Earthwalker', Eschscholzia 'Orange King', Echinacea 'Primadonna White', Craspedia, Cosmos 'Pied Piper', Cosmos 'Purity', Cleome spinosa 'Violet Queen', Chrysanthemum 'Rainbow'

Order seeds now from higgledygarden.com and quote the discount code GWW15 to get 15% off your shopping cart. Code valid until midnight 19 February 2016.

What are you growing from seed this year, and have you started sowing yet? Let me know on Twitter, or leave a comment below.

You snooze, you lose

It might still seem a bit dull outside, but we’ve somehow made it more than two thirds of the way through winter. So, when it comes to the garden, now’s not the time to be caught napping.

December is all mulled pies and minced wine – twinkly lights, good will and good grief, in equal measure, to all mankind. January cowers under a blanket of gloom and despondency with, if we’re very lucky, the odd glorious cold bright day to break through the murk. By February, it’s too easy to find ourselves succumbing to a creeping inertia brought on by the cold, the wet and the dark.

We must fight the dullness, kicking off the listless mood which can paralyse a gardener through a long winter. By the time February arrives, we need to be psyching ourselves up, taking advantage of every second of extra daylight in preparation for spring. Complacency can be a pitfall during the shortest month – barely four weeks long – by the end of which the gardening year will have begun in earnest. Experienced gardeners might even be forgiven for a fleeting sense of panic around now, knowing just how much there is to be done in so short a space of time.

l’m not concerned about the obvious tasks getting done in time – the pruning of fruit trees and roses, the mulching, the weeding, the almost certainly pointless bramble attacking sessions (in spite of last week’s post, I’m still gardening old stylee). It’s the next category of job where I’m likely to find myself caught out – the almost obvious things which, perfectly apparent on walking through the the garden, but which, in the absence of decisive and timely action, too easily get moved from “Oh yes, I can do that next week” to “Oh bugger, I’ll have to do that next winter”. Replacing the supports for my clients’ vines is an example of this, the issue being that if I don’t do this in the dormant season, the ageing fixtures will be torn out of the wall by another generous summer crop. Claret everywhere.

Then, just to complicate things, there are the tasks that are being brought forward by the mild winter. It’s t-shirt weather again today, and you don’t have to look far for signs of life. The phlox is leafing up nicely in one border of The Rabbit Garden, which means the rabbits won’t be far behind. Better get cracking with the protection – a not insignificant job that wasn’t in the diary for another few weeks yet. And – I’m still slightly in denial about this – the grass, which hasn’t really stopped growing, really could do with a cut. If the ground dries out enough, I’m going to have to break the mower out early.

This is beginning to sound as though I’m limbering up for a whinge, but not so. I’m as happy in the garden in February as I am at any time of year. The unglamorous nature of so many winter gardening tasks – the raking, the barrowing, the endless leaves – could seem like drudgery if you were to adopt a certain mindset, particularly over the dark days that top and tail the year. A few weeks of this, and most people disappear indoors for the duration, refusing to countenance the space beyond the back door until tempted outside again by the smell of some pioneering neighbour’s late spring barbecue. But we’re not most people. We’re gardeners, and we know that this routine stuff is what keeps us connected with our plants and gardens throughout the year, so that we’re on hand and in a position to tend or tweak should tending or tweaking be required. And yes, I’m quite aware of the many keen and vociferous advocates of a winter’s break with a spring catch-up, just as I’ve heard tell of those who insist on brown sauce rather than red in a bacon sarnie. What’s more, I’m happy to defend to the point of being mildly uncomfortable their right to exercise such eccentric lifestyle choices, always assuming no harm is done.

But you won’t catch me napping in February ’cos it’s cold and wet outside. Where would be the fun in that?

Planting in communities

I was feeling pleased with myself. At long last, I thought I’d succeeded in identifying why, although I clearly have a passion for plants, my enthusiasm doesn’t look like that of many of my peers in the horticultural world. You’ll have to take my word for it that this epiphany occurred five minutes before I discovered a review for Claudia West and Thomas Rainer’s Planting in a Post Wild World, and not five minutes after. Eventually, in this blog post, I get round to reviewing it myself.

Zeitgeist is a funny old thing. For the dedicated follower of fashion, it may bestow feelings of belonging, camaraderie, and even relevance. Meanwhile the philosopher, scientist, artist, or original thinker in any field, it can bite on the bum, as Herbert Spencer would discover when Charles Darwin took the plaudits for the theory of evolution*. For those of us who, like me, fall into none of these categories, it’s simply interesting to see how similar ideas appear to self-engender in several locations, more or less simultaneously, and apparently quite independently of one another.

I don’t think of myself as a plantsman. It’s not merely that there's a vast wealth of data that I need to acquire before I could feel remotely justified in thinking of myself in those terms – it’s more that I haven’t the slightest ambition to go about acquiring that information (I’m excluding pelargoniums here – everyone’s allowed a minor obsession or two). And yet it can’t be denied that I love plants. But while I find plants interesting, and from time to time will treat myself to a few new additions for the garden, I’ve no insatiable drive to acquire endless new specimens for my collection.

So, while I can appreciate and admire the particular details of an individual plant, for me the magic is in the moment when you put two or more plants together, and – what’s more – it doesn’t matter to me how supposedly ‘garden worthy’ or how humble the plants in question are, the power is in the combination. So a grouping of Cosmos 'Purity', Melianthus major, Cotinus coggygria 'Royal Purple' and Verbena bonariensis, or one of Dipsacus, Rudbeckia, Miscanthus and Delphiniums has the same potential excitement value as a patch patch of weeds that you might find at the base of a wall, or in the bottom of a hedgerow.

A designed plant community at Great Dixter. This combination wouldn’t occur in the wild, but it invokes an idealised natural landscape in the mind of the viewer

A less glamorous location, showing how closely plants coexist within naturally occurring communities.

Of course there’s nothing new in stating that planting combinations are key to making a garden zing. Good gardeners and designers understand this on an instinctive level, but many – very many – don’t. Even at the RHS shows, you’ll see blocks of monolithic planting, which is all well and good on the rare occasions where some kind of brutalist notion underpins the design concept. But all too often we see the clean contemporary lines of the hard landscaping paired with a kind of faux-minimalist design (I’ve referred to it as ‘plastic planting’ before), which bears little resemblance to true minimalism; not when you think of the music of Steve Reich or John Adams, where one constantly repeated phrase gradually meshes with another, continually shifting in and out of phase with one another, and creating new patterns all the while. This is what plants do, and do naturally.

Which brings me – and not before time – to the Planting in a Post-Wild World, by Thomas Rainer and Claudia West.

“There is a difference between the way plants grow in the wild and the way they grow in our gardens. Understanding the difference is the key to transforming your planting.”

Why should we want to transform our planting? Because, it is argued, so much of the way we go about the business of gardening now is both time and resource hungry – we plant individual, or small groups of plants, surrounded by bare soil, mulched to keep down competing plants (weeds), in soils which we continually seek to improve by the addition of fertilizers and conditioners.

Rainer and West point towards a planting of the future, characterised by a variety of species interweaving to form dense carpets of vegetation, a lack of bare soil, and evidence of a number of different ways in which plants adapt to their site, resulting in more robust, harmonious and diverse plantings which, critically, require less maintenance. Further environmental benefits, such as greater biodiversity, and increased potential for carbon capture and rainwater sequestering are both implicit and clear to see.

The authors call time on the sloppy thinking and cognitive dissonance evident in our simultaneous preaching of ‘right plant, right place’ while advocating large scale soil amelioration and mulching regimes. The notion of plant communities, defined as ‘related populations, not isolated individuals’, and the dynamics which operate within them over time and space, is central to the book’s premise, the repetition of the phrase becoming almost mantra-like over the first few chapters. But the scope of the book is greater than merely posing the questions and suggesting a new ideology: this is a practical volume whose chapters lead us on a journey, first setting the scene, then establishing some basic principles before detailing the phases of design, implementation and management (rather than maintenance).

This book articulates an optimism about the opportunities presented to gardeners and designers by our increasingly built-on landscape. Rather than become paralysed by mourning for what we have lost – and without deprecating the sincere and heartflelt grief we feel at the irreversible destruction of so much of our natural inheritance, the text assumes a forward-looking stance, and paints a picture in which the best of our efforts will see us working in partnership with nature in designing environments which are at once sustainable and full of meaning for all who interact with them.

After all of which, you might be left with the question: does this book really describe the future for planting in a post-wild world? It certainly describes a future, and one I’d like to think we can enthusiastically embrace in order to meet the challenges of greening our ever-increasing urban spaces. That this challenge will require a slight shift in thinking should perhaps come as little surprise. With this, we should be with Mr Scott of the Starship Enterprise:

It’s planting, Jim. But not as we know it.

* Spencer’s own concept of evolution was published in 1857, predating On the Origin of Species by two years. He even coined the phrase ‘survival of the fittest’ in a comment upon the latter’s work, but today his renown has been eclipsed by Darwin.

January in the garden

Winter arrived last week, bringing clear skies and cold air, frost and even a dusting of snow. Like the very best of house guests it’s set to depart too soon, leaving us in eager anticipation of the next visit. It’s good to spend time together. We really should do it more often.

Thursday’s planned morning of mulching fell victim to the mild conditions as, arriving on site, it became clear that the borders all needed edging yet again. There’s no point spreading out a luxuriant covering of well rotted manure over the borders only to scatter grass clippings over the top, and so, out with the edging shears again. They’ve never seen so much action at this end of the year.

Mulching delay

The soft ground is still soggy and compacts too easily when walked on, so while the edges are now crisp, I’ll have to wait for drier conditions to make them straight again, at which point a spot of aeration will be in order. You could of course argue that I shouldn’t be tramping about over a soggy garden at this time of year. You probably wouldn’t like my response.

By the afternoon the wind had turned bitter, the sky threatening snow – emptily, as it turned out – before Friday morning brought one of those perfect days for winter gardening; sunny, cold, the ground under a light frost but still workable. I find myself wishing every winter’s day could bring such conditions, how gladly I’d trade weeks of mild, slushy, muddy stuff for the necessity of wearing several extra layers (five and counting, and still feeling the chill) and losing the feeling in my knees and toes every so often. Briefly, I consider that perfect hibernal gardening conditions might cause my winter reading pile to swell to an unmanageable height, before realising that, in all honesty, it’s probably already got to that point. And anyway, that’s what the long, dark evenings are for, isn’t it?

A little light reading...

We’ve a few more days of cold brightness before the warmer air moves in from the west. Time for me to move away from the screen, and get back out there.

A prune with a view. A sunny day for cutting the dead wood out of the photinia

New year

Twelfth Night was yesterday. Decorations have been put away, lights switched off, front doors defoliated. Green plastic boxes stuffed with cards and crumpled wrapping paper line the bin day morning pavements, jostling for space with the relics of Christmas trees past. The holidays are done and dusted, and January is upon us.

They call it new year. We know this is wrong, that this is still a time for reflection on the year that has gone, that – ordinarily – we have dark, cold, grey weeks ahead of us before we welcome in the new season with the noticeable lengthening of the days and the rising of the sap. For Pete’s sake, it’s the middle of winter still. Who decided that this thing – this turning up of the calendar – would occur with such indecent haste, so soon after the turning of the year? There will be sound and sensible explanations for it – good reasons why they decided to declare the new year in January. But they’re not our explanations. Not my reasons.

So not yet, for me at least, a period of looking forward, though this is not far off now. Each day this week the post has brought another seed catalogue, even – joy! – some seeds. But I’m saving these a while. Just now, I’m taking stock, reviewing the catalogue of photos from the past twelve months’ gardening, wallowing in what went well, and noting down areas for improvement.

We gardeners get to make dreamy spaces. Here is one; the brief – make us a prairie garden where the veg patch was. Only with tree fruit. And soft fruit. So I did, pausing only to wonder if this kind of garden was A Thing, before realising that it didn’t really matter either way. That’s one of the benefits of having your own garden – you can make it what you will, according to your time and resources.

First I lifted, and barrowed, and tidied. There were a lot of paving stones. Then I began to carve new beds from the lawn – for the first hour or so, this is as satisfying and effortless as drawing with a fat, brown crayon on a huge sheet of green paper.

After a while, you begin to feel it, in your shoulders, down your back, in the tightness of your thighs and forearms. The turfing iron became my constant companion – so much better than a spade for this job – until one day I suddenly lost the knack, or so I thought, until I realised all that was needed was for me to rekeen the edge of the blade.

And day by day, the new garden began to take shape, turf lifted from one area relaid, rolled and watered to fit the contours of the new design, until the veg patch was no more than a memory.

There are situations in which a rotavator is a useful machine, though not as many as you’d think. This wasn’t one of them. The plan was always to mulch heavily, digging being called for only in the excavation of holes in which to put the plants, which began to arrive now in number. We’re fortunate to be only a few miles from How Green Nursery and, though by this time they were frantically busy with work for the RHS Chelsea Flower Show, Simon was able to fit me in between delivery runs up to London.

Grassy. A barrow full of Deschampsia and Miscanthus.

And then, the rabbits arrived.

In fairness, the rabbits had been there all along. We knew this, which is why we’d taken pains to consult lists of appropriately rabbit resistant plants. The rabbits clearly hadn’t read the same lists.

Rabbit-munched – Rudbeckia

Tough stems of Verbena bonariensis and Eupatorium maculatum, the hairy leaves of Rudbeckias and Echinaceas – all fell before the lapine hooligans. Grasses fared no better, the flowering tips of Deschampsia 'Goldtau' clearly being delicious, while not even Stipa gigantea got out of things unscathed. The plump flowering buds on Leucanthemums, left completely alone elsewhere in the garden, were demolished almost as soon as they appeared. A handful on our planting list were clearly unappetising; Actaea simplex 'Brunette', the scented foliage of Achillea 'Gold Plate' and Phlomis russeliana among them.

Rabbit-proof – Achillea

A regularly applied spray of chilli and garlic was found to be more of a seasoning than a deterrent. Green mesh structures appeared; a variety of forms made of plastic and wire, all pressed into service as the first line of defence against the rabbits. These were more successful, if unsightly – although the green colour went some way to mitigating the visual noise, they still intrude to a degree. But it’s a small price to pay and, as the plants mature, will become less of an issue.

Mesh, top right, protecting a clump of Deschampsia cespitosa 'Goldtau' from hungry rabbits

That was Year One. The new year brings into prospect the increased resilience of a more mature planting with established root systems, though I’ll still need to keep a watchful eye for damage. Good, solid and tough plants is what I want here – well tended, but not pampered or over-fed. We have a few backup plans, too, the least drastic of which involves planting a sacrificial crop close by, whilst at the other extreme...well. Let’s just hope it doesn’t come to that, for the sake of the rabbits’ 2016.

Your turn: what were your gardening highlights of 2015? Share the highs and lows with me on twitter, or in the comments below.

Jam tomorrow

New Year’s Eve, an hour or two till sunrise, the wind still howling around the house as it has for hours. It’s been a wakeful night, partly due to the wind, and partly due to us having forgotten to turn the central heating down, causing me to wake in the small hours feeling like a dehydrated prune.

I’ve used the restless hours to finish reading Roger Deakin’s Wildwood – it’s taken me an absurdly long time to get through it, savouring every page, and drifting into long daydreams of woods and trees and hedgerows, of exotic locations with towering walnuts and their heady, befuddling aroma, of wild apples in the East, and bush plums in the Australian outback, of generous, open-hearted people and comfortable old friends, and of time spent among trees, in solitude, but never alone. And throughout it all a prodigious knowledge of and respect for the skills and craftsmanship honed over centuries, and an implicit though rarely expressed concern that we might be on the cusp of throwing it all away.

And now the book is finished, I’m left with that sense of loss familiar to anyone who’s allowed themself to be immersed into a world between the covers. The best medicine for which is another book – five minutes later and, two more are on their way, Robert Macfarlane’s Landmarks and a secondhand hardback copy of Deakin’sNotes from Walnut Tree Farm, my delight at the convenience of Amazon tempered by a nagging thought that I’m overdue a penitential visit to my local indy bookstore.

“I’m sure I’ll take you with pleasure!” the Queen said. “Twopence a week, and jam every other day.”

Alice couldn’t help laughing, as she said, “I don’t want you to hire ME - and I don’t care for jam.’

“It’s very good jam,” said the Queen.

“Well, I don’t want any TO-DAY, at any rate.”

“You couldn’t have it if you DID want it,” the Queen said. “The rule is, jam to-morrow and jam yesterday - but never jam to-day.”

“It MUST come sometimes to ‘jam to-day,’” Alice objected.

“No, it can’t,” said the Queen. “It’s jam every OTHER day: to-day isn’t any OTHER day, you know.”

“I don’t understand you,” said Alice.

Through the Looking Glass & What Alice Found There, Lewis Carroll

Kettle. Tea. Still dark outside, and raining now, the first train trundling up to London, the sound carrying across the fields in the damp air. Everything’s louder when it rains. And now the birds are getting going – far too many birds, surely, for winter, reminding me that it’s not just gardeners who are still waiting for the cold weather to arrive. The prospect of a new year frost is held out like the promise of jam tomorrow. but in this crazy El Nino winter that has brought serious flooding to the north of the country (exacerbated, it has to be said, by the shortsighted land use policies of recent governments at both local and national levels), it’s hard to imagine that we’ll see anything other than a barely noticeable transition into a mild and wet spring. That said, the first week of January looks to be a chillier prospect than anything December had for us, though not quite sufficient to put a check either on the plants making an early appearance, or the persistence of garden pests and diseases, storing up trouble for the season to come. A friend tweeted a picture of a small aphid infestation in her garden a couple of days ago, and I don’t recall ever before having to swat away mosquitos on Christmas day.

Today, though, we’re promised clear skies and sunshine in Kent – a pleasant way to see out the year in the garden. Winter tomorrow.

The hellebores have been out for weeks.

Burn, baby, burn

There’s a cheer with a real fire that the civilising influence of several millennia can do nothing to dampen. It’s a primeval comforter, our response to it being hard-wired into us at some point on the evolutionary journey. The alluring blue light of smartphone or tablet might flirt with our attention and distract us from more constructive pursuits, but it can’t hold a candle to an open flame, lacking not only the warmth, but also somehow the substance.

I’ll often sit down of an evening and watch the play of the flames in the stove; it’s a decidedly superior way in which to while away the time, especially when compared to watching the telly, and the stories that unfold in the heart of the fire are more compelling by far. But this winter having been such a disappointment so far – so mild, and dreary – we’ve hardly had cause to light a fire at all, which is beyond miserable. Our one consolation for the awful darkness at the death of the year is the bright fire in our hearths; it’s a pitiful season that not only robs us of the daylight, but contrives to be too warm to make the lighting of a fire a daily event.

How glad is the gardener of a good blaze, though! Tediously mild or bitingly cold, there’s always plenty of material unfit for compost heap or shredder, and too unwieldy for the council’s green waste collection, that will amply acquit itself as fuel for a heartening burn to drive the dull drab grey away. I’m no cub scout and, much as I’m sure it would offend Messers Grylls and Mears, resort to firelighters and matches to get a bonfire going. But never, in the manner of one venerable assistant head gardener of my acquaintance, to diesel, poured liberally from an old red can. He was a fabulous character, a lovely man and an absolute walking encyclopaedia of gardening knowledge and experience, so it always came as a surprise to me when he reached for the accelerant, rather than beginning the process by the rubbing together of a couple of sticks. At least it wasn’t petrol. People who habitually start fires with petrol tend not to last very long.

Well contained

There are those who might look askance at my advocacy of the garden bonfire, pointing to the aggregate effects upon global warming of a nation of gardeners burning their winter waste. And they might have a point, if all of us did it every week. But I fail to see how the occasional, well tended and considerately managed fire could cause a problem. Besides which, I’ll only take lectures on the topic from those who have forsworn both meat and air travel*. I’m not sure how many bonfires I’ll get to a year’s worth of cattle farts and return flights to Lanzarote, but I’m willing to bet it’s a fair few.

Today has been damp, but tomorrow looks fine and I’ve high hopes of finding sufficient dry tinder and kindling to get a fire going. There’s always plenty of birch brash in my Wednesday garden, and that needs little encouragement to burn. All that remains is to pack matches, firelighters and hayfork, and pray the rain holds off overnight.

Can’t help seeing faces in things. A warm smile on the incinerator here.

*You’ll probably still get short shrift. But maybe a toasted marshmallow if you’re lucky.

’tis the season

The last week in November provides an ideal opportunity for such merriment, as several hundred garden broadcasters and writers descend upon the Savoy Hotel for the annual Garden Media Guild Awards. I snuck in for the second year running and, also for the second year running, was delighted to be shortlisted as a finalist in the Blog of the Year category. It’s a tangible affirmation not only of the work I’ve put into the blog over the past year, but also the enthusiasm and engagement of the community that’s grown up around the weekly posts. But while I’m both tremendously grateful and immensely proud of all of this, it didn’t make me blush half so much as receiving several generously and unexpected endorsements from gardening twitter friends (you know who you are) both before and after the awards were announced. A season to be jolly, indeed.

And, as winter follows autumn, itself turning into spring when the moment is right, it seems timely to confess that for a while now I’ve had a feeling that the blog in its current form is nearing the end of a season, and entering a period of transition. The hibernation period must necessarily be brief, but I expect this online collection of my garden witterings to emerge as a thing transformed, albeit with roots very much in the current iteration. I have in mind something slightly more than a refresh with, in time, some new features, tweaks to the structure, and a more open, airy feel about the place. At least, that’s the intention, with a view to launching early in the new year – a daunting, but exciting prospect.

In the meantime, I plan to keep these pages running, but do please excuse me if I should appear to be a little slower than usual to respond while I’m tinkering with things under the bonnet – a vehicular metaphor – time to give the blog a good winter service. ’tis the season for it, after all. fa la la la laa, la la la laaaa.

|

| Posh suit and shoes for hobnobbing on Thursday... |

|

| ....back down to earth on Friday. |

Taking steps

O, for a red brick path! Solid under foot, and easy on the eye. Throughout my various excavations in the garden, I’ve managed to unearth a small pile of imperial red bricks in fair condition, but nowhere near the quantity I’d need for the path. I keep a beady eye out for the small ads, and auctions of reclaimed bricks on eBay, but somehow, something more pressing and grown up always seems to require paying for – a new boiler, or a replacement cross-member for the chassis on the venerable land rover. Even – dare I say it – plants. And in the meanwhile, sure as eggs is eggs, the path turns to mush.

This winter, I’m taking steps to avoid the quagmire. A roll of grass reinforcement mesh – the kind of stuff you find lurking just beneath the sward of the overflow car park at a country fair – which I unrolled and immediately split down the middle with the aid of a pair of tin snips.

|

| Snip. Figured I only needed a 50mm strip down the centre of the path |

|

| Not pretty, but already disappearing |

Hairy bittercress

The admission causes me a degree of discomfort, having on numerous occasions made my admiration for weeds a matter of record, but even I find it hard to wax lyrical about hairy bittercress.

It’s a nuisance in the nursery – perhaps not to the same degree as the liverworts which blanket the surface of the growing medium, but nonetheless a pretty ubiquitous presence, stealing nutrients and acting as a host for numerous glasshouse pests.

It’s also something of a gremlin in the garden, and you need be in no doubt that you will have hairy bittercress in your garden. Possibly also its cousin, wavy bittercress (Cardamine flexuosa) – very similar in appearance, though the small white flowers have six stamens to the four of its nominally more hirsute relative (the hairs on the leaf margins and axils aren’t particularly noteworthy, in spite of the name). As long as extremes are avoided, bittercress can’t bring itself to be discerning over the pH of the soil, seeming just as at home in acid, neutral or alkaline conditions, and will grow in shade, part shade or sun, in either moist or dry conditions. A hardy annual (C. flexuosa sometimes persisting as a short-lived perennial) it behaves as an ephemeral weed, producing several generations in one growing season, and each plant can produce up to 5,000 seeds.

|

| Not wavy, but downy. Four stamens, so Cardamine hirsuta |

Common names include lambs cress, spring cress, hoary bittercress, wood cress and flickweed. This last name is particularly descriptive of the manner in which the plant goes about dispersing seed, a trick which anyone who has carelessly reached for a plant which has gone to seed will be only too able to describe. The characteristic long, thin seed pods (known as a siliqua), common to many members of the brassica family, split open when dry, ejecting their contents with some force and scattering seed over a distance of up to six feet, unless prevented from doing so by some intervening object. Such as the face of a surprised gardener.

|

| The ripening seed pods, or silique, ‘overtopping’ the flowers |

Let me know what your thoughts are on hairy bittercress, either on Twitter, or by leaving a comment below.

A walk in the woods

Hawthorn, field maple, sycamore, sweet chestnut and hazel – each turns its own rich shade of yellow gold before releasing its leaves. We wandered along gilded corridors between stands of coppice understory, shafts of bright sunlight piercing the ceiling and spotlighting individual works of art – here a patch of moss on the trunk of tree, there a single leaf picked out on the muddy forest floor.

A gallery of sylvan wonders. Dogs welcome.

Great Comp Autumn Extravaganza

I arrived in bright sunshine to find the borders in their full late-summer glory, grasses and perennials having filled out and drawn themselves up to their full stature, and giving every impression of returning the admiring glances of the visitors with something approaching condescension, arising from a pride in the knowledge that this, of all moments in the year, is the moment in which they look their absolute best. I think we can allow the contents of the borders their lofty attitude; they look very fine indeed.

On to the plants. A goodly selection of specialist nurseries, although I had the impression that there were fewer than at the Spring Fling. Sufficient in number to provide temptation to a gardener with a roving eye, however.

I was half hoping to track down my unicorn, a plant that I’ve been after all year since one of my clients saw it in the prairie gardens at Wisley. I’d seen a few diminutive pots of the Arkansas bluestar, Amsonia hubrichtii, at Dixter last weekend but, having left my wallet at home, I was saved from having to buy the things – something of which I was quite glad, not having been entirely confident of my ability to see the tiddlers through the winter. Amsonia seems to be growing in popularity – a mainly North American relative of the periwinkle, although not sharing the vinca’s slovenly posture it bears its light blue, star-shaped flowers in early summer on upright stems. It hasn’t been hard to get hold of Amsonia tabernaemontana, and I spied A. ciliata on the stand of Hardy’s Cottage Garden Plants at Chelsea earlier in the year (Rob and Rosy stock several species, I’ve subsequently found).

But Hubricht’s bluestar has much thinner, needle-like leaves, and in autumn, it does this...

|

| Amsonia hubrichtii in full autumn colour |

Today’s offerings, as you might expect from a plant fair in October, were distinctly shrubby, with the odd climber or tree thrown in for good measure. You might think this would be boring but, in that opinion, you’d be wrong.

I’m always a bit of a sucker for an attractive ilex, and the prickly pineapple holly, Ilex aquifolium 'Myrtifolia' bears perfectly formed, glossy green leaves about an 3cm long by 1cm wide, bristling with spines. It’s a neat, compact specimen, with the young shoots exhibiting a slight purplish tinge.

|

| Ilex aquifolium 'Myrtifolia' |

|

| Euonymus fortunei 'Wolong Ghost' |

|

| Trachelospermum jasminoides 'Waterwheel' |

|

| Frangula alnus 'Fine Line' |

|

| Sassafras albidum. Used to flavour rootbeer |

|

| What’s that smell? Probably Cercidiphyllum japonicum |

Container Gardening with Harriet Rycroft, week 4

ADVERTISEMENT FEATURE

The final week of the container gardening course with My Garden School. ‘Summer Luxuriance’, it’s entitled, and brimful of information to help you take full advantage of the long days and warm temperatures. Containers should be bursting with fabulous foliage and jewel-bright punches of floral colour from June well into September and beyond, and Harriet guided us through with advice on plant selection, what to grow in sun and shade, as well as some useful tips and tricks, such as growing climbers in pots, and using them to weave in and out of the display.

Irrigation is of course of prime importance during the hottest months, and watering methods were covered, along with other maintenance tasks such as feeding and deadheading.

Once again I was thrown something of a curve-ball by the assignment, in which we were asked to base a container display around our favourite colour. I’ve come to the conclusion that I don’t have a favourite colour, tending to base my planting ideas around either harmonious or contrasting colour combinations, rather than monochromatic schemes, which can seem a little flat. So, I have favourite colour combinations to which I return time and again – greys and pinks, greys and yellow, lime green and deep red tones, to name but a few. If there’s one colour to which I’m drawn, it would those tones variously described as black, or burgundy, or deep red-purple – as with the foliage of Cotinus coggygria 'Royal Purple', or Actaea simplex 'Brunette', for example – and so I took this as my starting point.

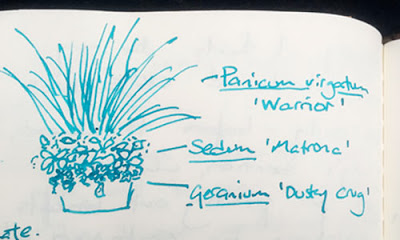

The brief involved suggesting three plants, each of a different habits (tall, bushy and spreading or trailing) that feature the chosen colour in either foliage or flowers. After some head scratching, the following scribble emerged.

My tall plant is the switchgrass Panicum virgatum, which grows to 1.2 metres, although younger plants in a container are less likely to achieve the full height. The glaucous grey leaves will give some relief to the otherwise monochrome scheme, with deep, metallic red flower heads in August.

|

| Panicum virgatum 'Warrior' |

|

| Sedum 'Matrona'. Image © Crocus |

|

| Geranium 'Dusky Crug' |

I’m fond of this combination, but aware that it’s not perhaps quite in the spirit of the brief, reaching its peak in August and September – a pot for late summer and early autumn. If I’m to bring the season of interest forward into early summer, I could stretch the colour theme a little, to embrace deep red stems and foliage and/or crimson flowers. Then we could try a combination built around Lobelia cardinalis 'Queen Victoria', with Heuchera 'Autumn Leaves' occupying the middle layer, above the trailing deep green foliage and of Pelargonium 'Mexican Beauty' this would work well in partial shade, and although the lobelia would be the last to come into flower (August again), there would be plenty of interest throughout the period with the deep maroon of the stems, over the vibrant shades of the heuchera foliage (softened slightly by the white flowers from June) and the longer flowering period of the ivy-leaved pelargonium.

|

| Lobelia cardinalis 'Queen Victoria'. Image © Crocus |

|

| Heuchera 'Autumn Leaves'. Image © Crocus |

|

| Pelargonium 'Mexican Beauty'. Image ©Fibrex Nurseries |

My imaginary courtyard pot display is now looking rather flamenco-inspired, with this container situated in a slightly sunnier spot than the partially shaded area enjoyed by the panicum-sedum-geranium combo, along with pots full of Dahlia 'Bishop of Llandaff', Cosmos atrosanguineus, Aeonium 'Schwartzkopf' and Ricinus communis 'Carmencita'. With plenty of green in between, and a large jug of sangria.

With thanks to Crocus and Fibrex Nurseries for the use of images.

Details at Great Dixter, and Planty Fare

I visited yesterday ostensibly for the autumn Plant Fair, another fantastic event which sees the gathering together of some fine specialist nurseries from the UK and beyond, with a programme of regular talks from the nursery-folk throughout the weekend and, of course, rather good food. On arriving I was pleased to see a friendly face, although Rosemary on the Hardy’s Cottage Garden Plants stand was in mid flow, drawing the attention of a crowd to the benefits of some of her stock. First up was what I would until recently have called Aster turbinellus, my parents would still call a Michaelmas daisy, and Rosy was at pains to point out has been reclassified as Symphyotrichum turbinellum (why use two syllables when you can use five?). Growing to four feet tall, it has a lovely open habit, is fairly mildew resistant, and, as I can testify having planted several in a garden besieged by the rotten creatures, will hold its own against rabbits (although they will have a good go at it).

|

| Rosy Hardy explaining the joys of botanical reclassification |

|

| Symphotrichum turbinellum from Hardy’s Cottage Garden Plants |

|

| Physocarpus opulifolius 'Lady in Red' from Hardy’s Cottage Garden Plants |

|

| The Binny’s Plants stand at Great Dixter |

|

| Derry Watkins of Special Plants, chatting to a fine beard |

|

| The Great Dixter Nursery stand, about 50 yards from the actual nursery |

|

| The porch displays are always changing. Worth the visit alone. |

|

| A different kind of hawthorn. Crataegus orientalis |

|

| Pelargonium sidoides on the far right, Persicaria 'Purple Fantasy' two points to the left |

|

| Entering the Peacock Garden |

In the High Garden, I had a moment of affirmation. I've been mildly berating myself for undertaking a slightly bonkers brief early in the new year, to transform an old vegetable garden into a prairie-style planting, but incorporating the fruit trees and soft-fruit. Standing here, however, I felt justified and, knowing this space so well, I’m fairly certain that it must have been there all along, deep in my subconscious, preventing me from trying to talk my clients out of the idea.

|

| Fruit trees, grasses and prairie style perennials |

Climbing down the steps through the hedge into the orchard garden. What a treat.

Descending again to the long border, and another lesson for me with this openly pruned golden lonicera, echoing the form of the miscanthus in the background. Where I might feel pressure to clip this tight, how much more charming to allow it the space to breathe and assume an open shape. Artfully done, though, L. nitida being notoriously unruly when allowed free reign.

More lessons. I will use a golden spiraea as a blob in a border, but I hadn't thought to allow the form to flow and merge with an erysimum, let alone drape it around with nasturtiums.

Finally, for this trip, an encounter with a rather revolting variegated phlox, which nonetheless proved to be just the thing needed. Now, I can’t say with any certitude that the variegated phlox is a thing which should by law be allowed at all – I have my suspicions that quite the contrary should be the case. But on the long border, it somehow managed to ease a transition from predominantly warm colours to a patch of much cooler, greys, blues and pinks, which might otherwise have seemed to jar. Food for thought – I'm still not entirely sure what I think about the plant, or even about this patch in the border from which the colour appears to have bled, but that is one of the wonderful things about the way Fergus and his team are continually experimenting here, reviewing every element and assessing the role it plays within the whole.

|

| Add caption |

Container Gardening with Harriet Rycroft, week 3

ADVERTISEMENT FEATURE

I always knew that the third week of this course was where I’d begin to find things a little more challenging – in fact, this tutorial was one of the main selling points of the course for me. We’ve been looking at planting containers for winter and spring interest, something I’ve never had trouble with in the past, but largely because I use a far less sophisticated approach. Typically, I’ll create containers for autumn and winter, using plants with interesting evergreen foliage and impressive berries to create the backbone of any display for several months, around which pots of more short-lived seasonal colour can be introduced – cyclamen before Christmas, tulips, narcissi and hyacinths later in the new year.

This modular modus operandi is reasonably foolproof, having the advantage that, as long as you get the main plants right, you can tweak by moving the smaller pots about, removing anything that isn’t performing quite as well as you’d hoped, and perhaps redistributing containers to draw attention to a particularly pleasing element. It allows both for serendipitous discovery, and wiggle room, and I’d be happy to recommend this way of working on these grounds alone, if it wasn’t for the fact that it’s more or less how the wonderful displays in the porch at Great Dixter are put together. And if it’s good enough for Dixter, it should really be good enough for anyone.

That said, there is another way to plant in containers – and, happily, it can be used alongside such a modular approach as I’ve become used to. The only slight fly in the ointment is that it’s a little more involved, requiring both more planning, as the planting needs to present interest over a longer period of time, as well as a good deal more commitment, there being less wiggle room once everything has been planted in the one container. I’ve seen Harriet’s plantings, both at Whichford and online, and have no doubt that this is a system I need to master in order to take my container displays to the next level. As elsewhere in the garden, there are few things more impressive than seeing an effortless scheme seemlessly transitioning from one season of interest to the next, a continual dance as one performer retreats into the wings, and another steps forward to command stage. This is succession planting in pots. Time to play with the big kids.

The first things to consider when planting any container for the cooler months is drainage. In winter it’s all too easy for the soil to become waterlogged, and no plant likes to sit with its feet in water1. To that end, make sure that whatever container you’ll be planting into has adequate drainage holes, and be sure to use a free draining compost, incorporating horticultural sand or grit – I’d be happy to use a ratio of one measure of sand to four of compost in order to make conditions a little more sharp. Add no water retaining gel or crystals – great in summer, but deathly in winter – and avoid composts to which these ingredients have been added (it should be clearly evident on the outside of the bag, probably with some daft marketing slogan “Now with ADDED Wet-Water Waffle” kind of thing).

But now comes the crunch, and, as so often seems to be the case with these things, the key would seem to be a matter of perception. Instead of viewing the container and its contents in two dimensions (front to back and side to side), we need to be mindful of four. The third dimension allows us to correctly position within the pot the bulbs which will be so important for creating interest and change in the spring – larger bulbs, like tulips, at a greater depth than smaller bulbs, such as crocuses, for example. With the introduction of a fourth dimension, time, we have to consider the display over a matter of weeks and months, as the initial winter planting gives way to the delicate freshness of early spring, and in turn the vibrancy of mid- to late-spring.

It makes for a much more crowded pot than I’m used to, but the lecture notes were full of advice as to the relative planting densities and depths for different bulbs and, as ever, Harriet’s been on hand in the online classroom to answer individual queries in person, and to discuss the other material covered this week, including colour schemes and arranging containers.

This week’s assignment asked us to create a planting plan for a pot 60cm wide by 30cm deep, providing winter interest while using bulbs to extend the season into spring. I’ve opted for a silvery grey colour scheme over winter, with white flowers, introducing pinks and blues as the weeks pass into spring.

|

| Planting plan of the top layer of evergreen perennials and shrubs |

The top layer features evergreen perennials and shrubs that will persist from winter through spring. Planted fairly densely, as there won’t be an awful lot of growth over the period for which this container will be on display.

|

| A rather ropey detail shot of Calocephalus brownii 'Silver Bush' |

|

| Heuchera 'Peppermint' Little Cutie Series. Image © Heucheraholics |

|

| Cyclamen hederifolium 'Album' |

|

| Senecio cineraria 'Silver Dust' |

The bulb layers next, in order of descending depth.

|

| Crocus 'Ladykiller'. Image © Crocus |

|

| Muscari armeniacum Image © Crocus |

|

| Fritillaria mealagris var. unicolor subvar. alba. Image © Crocus |

|

| Tulipa 'Flaming Springgreen'. Image © Crocus |

|

| Tulipa 'Foxtrot' |

|

| Narcissus 'Fruit Cup'. Image © Crocus |

With thanks to Crocus and Heucheraholics for the use of images.

1Except maybe the swamp cypress Taxodium distichum, and even they like to leave at least their knees out of the water. You’d need a very big pot for one of those, though.

Do have a look at the My Garden School website, which is still running its Back to School campaign for 15% off all £145.00 4 week online courses in October. (Course start dates: Wednesday 7 October 2015). Click here and remember to use the code MGSBTS at the checkout for the discount.

about me

I’m delighted you’ve found your way here, and hope you’ll stay a while. If there’s a common theme running through these pages, it’s something to do with my belief that gardens – and gardening – have the power to provide us with the stimulation and solace all too easy overlooked in the relentless routine of modern living. All the time I spent behind a desk in comfortable air-conditioned offices, many with fabulous facilities, I’d find my mind wandering to the garden. Comfort, I was beginning to understand, is not all it’s cracked up to be.

For me, spending time outside is tremendously energising. To rest a hand against the bark of a tree, to feel the whispering touch of wet grass or the crunch of fallen leaves beneath my boots; to suck in great lungfulls of air, and deal at first hand with the capriciousness of the British weather – this is where I want to spend my days. To be among plants, too; watching how they grow, form communities and interact with each other, with us and with the wildlife with which we share a space. You’d expect me to be in my element in the countryside, wandering through the Kentish fields and the surrounding woodland, but, walking back into town, through first the farms and then the outlying housing estates, it seems that these relationships become more apparent as the density of housing increases. In no small way this gives me hope; and while many people feel despair and anger at the eroding of planning regulations, and the talk of growing urbanisation, I see positive signs. The relationship between people and plants has been taken for granted for too long now, but – just in time – there is evidence that we are beginning to remember what was had been common knowledge for centuries. Throw in an understanding of the soil, and there might just be hope for us all, though admittedly we’re cutting it pretty fine.

Working in gardens has allowed me to expand the boundaries of my office – no walls, a ridiculously high ceiling, and the most intricately woven carpet imaginable. Writing about gardens seems to follow naturally – I can’t garden without thinking, and I can’t think clearly without writing. As something occurs to me, I’ll scribble it into the notebook extracted from the depths of some mud and twig-filled pocket, returning to my computer at the end of the day to input these collected ideas and half thoughts, maybe to arrange them into a blog post, an article, or a short twig for into-gardens. Only now I find it almost unbearable to sit for long at my comfortable desk in my nice warm study. My comfort waits for me beyond the back door, whatever the weather, and the garden is calling.

|

| With Bill the border terrier, under gardener, charmer, and insatiable plant muncher |

Gardening advice and writing Do get in contact if you have any gardening queries by clicking here, and I’ll do my best to answer them. If you’d like me to provide gardening related copy for your publication or website, or are interested in having your product reviewed on the blog, please send me an email at info@andrewobrien.com.

Of minor reshuffles, and free plants

Along with an abrupt drawing in of the evenings, the cooler night time temperatures seem to have descended upon us all of a sudden – the greenhouse thermometer showing below four degrees a couple of days ago. The knowledge that this happens at more or less the same time every year does nothing to diminish the mild sense of surprise we feel at the change; in company with the bees in the ode, we’d come to believe the warm days would never cease.

|

| Apple time. Part of our first harvest of Laxton’s Superb |

September, then, is a good time for a garden reshuffle. But it’s also a time for discovering you have a wealth of free plants, in the form of perennials crying out to be divided. It is, of course, a matter of accepted horticultural best practice to divide your perennials every few years in order to restore vigour to the individual sections. Apart from anything, it helps to avoid the potential of having ever-expanding clumps of a single plant, with very little growth in the centre. So far, so strokey-beard. But, aside from earning you brownie points with the RHS (which do actually exist and can be exchanged for baked goods in any of the restaurants at the society’s four main gardens)1, the joy of discovering that your stock of plant material has increased, with very little effort on your own part, is hard to describe to any non-gardener, but all too easy to understand for anyone who’s ever felt the pang of parting with six quid for a single two litre pot of some precious specimen.2

Earlier today it was necessary to cut back a small Persicaria affinis (‘Donald Lowndes’, if memory serves), which was in the process of escaping from the border and making its way across the drive. This attractive, creeping plant forms a semi evergreen mat with flower spikes ranging from white, through light to deep pink through summer and into autumn. It’s great for the front of a border, although once established it will need to be kept in check, as it produces roots from every node that comes into contact with the ground, a characteristic which gives you plenty of opportunity to successfully root cuttings with minimal effort. Once I’d trimmed the plant back to its allotted space, I removed the flowers from my cutting material – producing seed can be an exhausting process, and I’d rather the newly establishing plants concentrate their efforts on making healthy root systems.

Appropriately enough for a drive edge, this Persicaria is sufficiently robust to withstand being driven over. However, as it’s shallow rooted, and the planting holes little more than a scrape, today I used long steel pins to hold each section in place until the roots have taken hold.

Free plants, perfect weather, and rejigged garden. Somebody pinch me.

1Utter nonsense.

2That said, and providing it’s not coming out of the housekeeping budget3, noone should have any qualms about spending this kind of money on a plant from one of the many independent nurseries forming the backbone of the horticultural trade in the UK. This is what it costs to raise and nurture a plant to a saleable size in a retailable condition, while at the same time maintaining a viable business, run by experts in the field, with employees and bills to pay. Shelling out this kind of money – or more – at any of the larger chains, where you might expect economies of scale to be passed on to the customer, requires a different set of decision making criteria.

3On the occasions when buying plants can threaten to compromise the housekeeping budget, there are plenty of other options. Plant swaps, car boot sales, kindly neighbours, friendly gardening types on Twitter – gardeners are by nature a generous bunch, and keen to share.

Container Gardening with Harriet Rycroft, week 2

ADVERTISEMENT FEATURE

What’s the difference between growing in containers, as opposed to growing in the ground? I’ve already written about how there’s less margin for error with a plant in a pot, the rootball having access only to the nutrients available in the container, and that much more vulnerable to sudden changes in temperature. In this week’s lesson, we were again considering the materials used to construct containers, but this time rather than from a purely aesthetic point of view, we’ve been looking at how, for example, a plastic or metal pot will typically have less thermal insulation than one made of good quality terracotta or stone, and how this should affect how you think about siting different containers.

Just as you need to develop an awareness of different microclimates in your garden when planting in the beds and borders, so too this needs to be factored in when planning displays of containers. Not just things like aspect, the location of frost pockets and wind tunnels, but also the potential for strong gusts to be bounced off walls and corners against which pots are placed, potentially causing harm to plant material through air turbulence. And, while you may think that your treasured plants are entirely independent of the ground, being safely ensconced within their pot and with roots nestled into your choice of an ideal growing medium, it turns out that the hard surfaces on which the containers are standing can still have a bearing on how well (or not) the plant thrives. As an example, and rather like an inverted version of the storage heater in my old Muswell Hill bedsit, a dark-coloured ground surface will absorb heat during the day, and slowly radiate the warmth back out at night. I remember this arrangement was pretty hopeless for me, as it meant the bedsit was toasty during the day when I was out at work, and freezing during the evening and night, but careful attention to the needs of your plants should mean that you can take better advantage of the principle.

Practical matters covered this week also included arranging containers in groups, watering and drainage, including the thorny issue of crocks, and the desirable properties of a good compost. Already having packed quite a lot to pack into one week, Harriet ended the tutorial with a consideration of what to look for when selecting plants for your containers, with criteria including foliage, flower and form, as well as texture and habit, and seasons of interest. Much to remember, and to help it sink in, this week’s assignment asked us to choose four perennials or shrubs which we thought would earn their keep in a container display.

Here are my choices.

Sarcococca confusa

Perhaps the least fancy Sarcococca, the Christmas box is nonetheless a plant I wouldn’t be without, growing it both in the ground and in containers. An evergreen shrub with a potential to grow over a metre in height after many years, I treasure it for its deep glossy, spear-shaped leaves, and the clusters of black berries. But mostly for the rich, heady, vanilla fragrance of its tiny white flowers in the depths of winter, filling the air with a delicious, warming scent at the most miserable time of year. During the spring and summer months, it lurks within the groups of containers, overshadowed by more flamboyant flowers and foliage, but once the tender things have been put to bed, it begins to come to the fore.

|

| Close-up of Sarcococca confusa. Sadly not scratch-and-sniff. |

Euphorbia characias subsp. wulfenii

This evergreen subshrub might not be the rarest of specimens, but it certainly earns its place in many different settings. Growing to 1.5m in height, and often rather larger around, the most striking feature for me is the colour – grey-blue foliage, topped with huge acid green flower heads in spring which persist for months. It’s not known for its fragrance, but having worked around it in several locations, I can confidently announce that it gives off a pronounced smell which might be described as bitterly earthy, or woody, but which reminds me of nothing so much as coffee grounds.

|

| Euphorbia characias subsp. wulfenii in flower. Less yellow, more blue in real life. |

Melianthus major

The most tender of my selections, practically herbaceous in my part of the UK, but growing as an evergreen subshrub in climates more akin to its native antipodes, where it has become something of a weed. Here, we love it for its large, pleated glaucous foliage with deeply serrated edges. I was once told by the head gardener of one of our major gardens that it wouldn’t flower in the south east of England, but mine decided to contradict this pronouncement, producing a massive maroon flower spike that November. Just before the frost and the wind reduced the entire thing to black mush.

|

| The leaves of Melianthus major. Remember, not all peanut-scented things are edible. |

Fatsia japonica

I have heard this glamorous relative of ivy sneeringly classified as a ‘carpark plant’. But, as every plant so labelled is an utterly reliable, unfussy, robust and attractive affair presenting year-round interest, I don’t see it as anything to be sniffy about, and I can’t get enough of its large, glossy palmate leaves. Even better, in summer, older plants flower with the most eerie-looking white umbels. A statuesque presence, in the ground it will happily grow to eight feet in both height and circumference, although in a container it will assume more modest proportions. Happy in shade, dry or damp, it will provide a luxuriant, tropical backdrop to any planting all year round.

|

| Glossy palmate leaves of Fatsia japonica. |

Do have a look at the My Garden School website, which is still running its Back to School campaign for 15% off all £145.00 4 week online courses in October. (Course start dates: Wednesday 7 October 2015). Click here and remember to use the code MGSBTS at the checkout for the discount.